The Operating Partner Compensation Crisis: Why Traditional Models Are Failing and What Top Firms Are Doing Instead

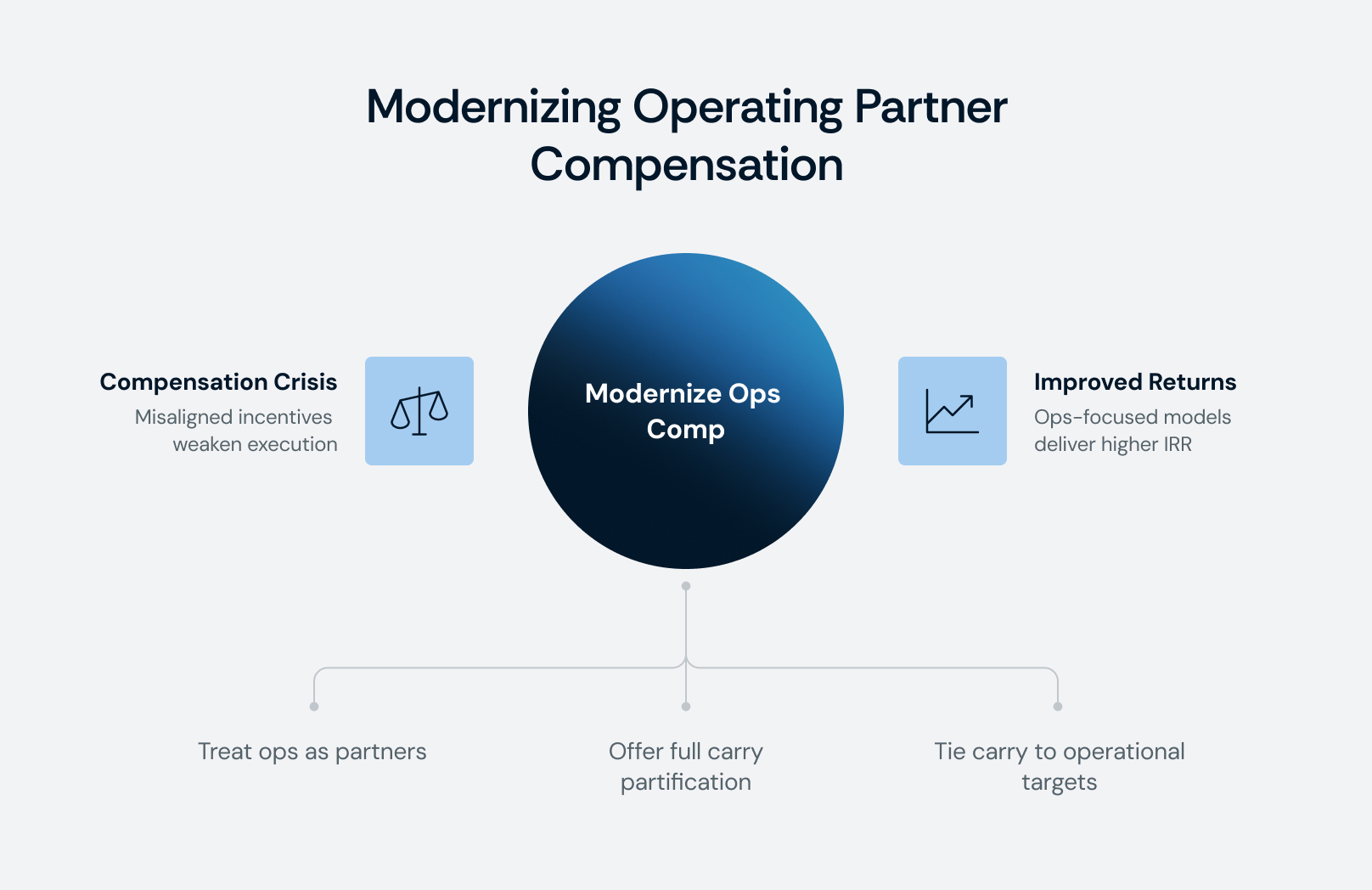

- Ops now account for ~47% of value creation—but comp structures still favor deal teams.

- This misalignment weakens execution, fuels attrition, and sends the wrong message to LPs.

- Senior ops leaders increasingly receive carry (80–92%)—but true parity is rare.

- Leading firms (Vista, Bain, KKR) treat ops as partners—with aligned economics and influence.

- Ops-focused models consistently deliver 2–3% higher IRR—$10M–$30M in extra value per $1B fund.

- This brief offers benchmarks and frameworks to help firms modernize ops comp—and outperform.

The private equity industry faces a compensation crisis that threatens the very foundation of modern value creation. Operating partners now drive 47% of returns in buyout deals—nearly three times their contribution in the 1980s (Developmentcorporate, PwC)—yet their compensation often trails deal teams by 30–50% at equivalent seniority levels.

This misalignment creates organizational dysfunction, fuels retention problems, and signals to limited partners that operational excellence is marketing rhetoric rather than strategic commitment.

The stakes extend beyond fairness. Firms that fail to offer competitive operating partner packages face a cascading set of problems: top operational talent defects to competitors or corporate roles, portfolio companies receive inconsistent support, LP confidence erodes, and the firm's competitive positioning deteriorates in an environment where operations have become the primary driver of returns. Meanwhile, sophisticated firms that have solved the compensation equation—treating operating partners as true partners with full carry participation—are winning the talent war, outperforming on returns, and finding fundraising significantly easier.

The fundamental issue is that compensation structures lag the strategic reality of private equity in 2025. Financial engineering now accounts for only 25% of value creation, down from over 50% in the leveraged buyout heyday (Developmentcorporate +3). With interest rates elevated and purchase price multiples near historic highs, the ability to transform portfolio company operations separates winning funds from mediocre ones. Yet many firms still structure operating partner compensation as if operations were a supporting function rather than the core product. This disconnect undermines execution, creates cultural conflict between deal and operating teams, and leaves firms vulnerable to competitors who recognize that properly incentivized operating partners generate returns that dwarf their cost.

This article examines the full scope of the operating partner compensation challenge—from its historical roots to specific benchmarking data across fund sizes—and provides actionable frameworks for firms ready to modernize their approach. The message is clear: firms that continue underpaying operating partners are not just creating HR problems—they're systematically destroying value and competitive advantage.

From Consulting Afterthought to Strategic Imperative

The operating partner role emerged from private equity's painful recognition that financial engineering alone could not sustain returns. In the 1980s leveraged buyout boom, deals succeeded primarily through leverage arbitrage and multiple expansion, with operational improvements contributing a mere 18% of value creation. Umbrex +2

The operating partner role emerged from private equity’s growing realization that financial engineering alone couldn’t sustain returns. In the 1980s LBO boom, deals relied heavily on leverage and multiple expansion, with operational improvements contributing just 18% of value creation (Umbrex +2). Operating capabilities were an afterthought—retired executives brought in sporadically, paid ad-hoc consulting fees, with no long-term alignment.

This model fell short as markets evolved. Clayton, Dubilier & Rice pioneered the formal operating partner model in 1978, partnering with seasoned industry executives. But for decades, the approach remained niche (Umbrex). The late ’80s buyout bust exposed the limits of financial engineering and forced PE leaders to focus on sustainable value creation. As Carl Ferenbach of Berkshire Partners put it: “Once we started to think about growth instead of just cash flow, we then had to think much more about strategy and management” (Umbrex).

The 2000s brought institutionalization. KKR launched Capstone in 2000, building an in-house team of 100+ operating professionals (Umbrex). TPG founded TPG Ops in 1995, becoming one of the first mega-funds with systematic operating capabilities (Umbrex +2). By the mid-2000s, firms like Blackstone and Bain Capital were investing heavily in operating teams. The 2008 financial crisis further accelerated the shift—cheap debt was gone, and operations became central to value creation (Umbrex).

Yet compensation structures didn’t keep pace. Through the 2000s and 2010s, many operating partners were still classified as contractors—paid via 1099s, expensed to portfolio companies, often without carry or benefits. This created clear misalignment: no skin in the game, no participation in firm economics, and a message that operations mattered—just not enough to share the upside.

The SEC’s 2014 “Spreading Sunshine in Private Equity” speech by Director Andrew Bowden crystallized the issue. Bowden noted that while operating partners often appeared as full members of the team—officed with the GP and working exclusively for them—they were typically not paid by the firm itself. Instead, compensation was expensed to funds or portfolio companies (accordion +4). The disconnect between operational rhetoric and economic reality was exposed.

The shift toward full partnership began in earnest in the 2010s. Leading firms started moving operating partners onto W-2 status with base pay, performance bonuses, and—critically—carry participation. By 2024, Charles Aris data shows 80–92% of senior operating partners are carry-eligible, though allocation remains contentious (charlesaris). The evolution from contractor to partner reflects operations’ rise as a core value driver—but the transition remains incomplete. And that gap now threatens execution, alignment, and ultimately, returns.

What Operating Partners Actually Earn Across the Market

Understanding the compensation landscape requires examining detailed benchmarking across fund sizes and seniority. Two of the most comprehensive datasets are the Heidrick & Struggles 2024 North American Private Equity Operating Professional Compensation Survey (251 respondents) and the Charles Aris 2024 Private Equity Portfolio Operations Compensation Study (177 respondents).

Entry-Level (Associate / Senior Associate)

- Base salaries: $135K–$235K

- Bonuses: $30K–$160K (typically 40–60% of base)

- Total cash: $200K–$300K

- Carry participation: 10–17% receive carry, a major jump from pre-2020.

- At a 2x return, carry value ranges from near-zero to $300K.

Vice President

- Base: $239K–$329K

- Bonus: $139K–$201K (50–90% of base)

- Total cash: $340K–$470K

- Carry eligibility: 29–54%

- Carry value (2x return): $1.1M–$2.9M

- Total package at $10B+ funds can approach $600K.

Principal / Director

- Base: $350K–$420K

- Bonus: $184K–$343K (60–100%)

- Total cash: $500K–$750K

- Carry eligibility: 57–79%, with values from $2M–$2.8M (and $8M+ at large funds).

Operating Partner / Managing Director

- Base: $340K–$755K (most cluster at $450K–$600K)

- Bonus: $123K–$1M+ (75–125% of base)

- Total cash: $750K–$1.6M

- Carry eligibility: 80–92%, with values from $2M to $23.6M (typically $3M–$8M)

Head of Portfolio Operations / Managing Partner

- Base: $410K–$740K

- Bonus: $185K–$1.8M

- Total cash: $1.2M–$2.4M

- Carry participation: ~100%, with 2x values of $6M–$20M+

Fund Size Impact

- < $500M: $518K base / $248K bonus / $8M carry

- $1–5B: $537K base / $238K bonus / $3.1M carry

- $5B+: $590K base / $238K bonus / $7.8M carry

→ Larger funds offer higher cash, but carry is the differentiator.

Bonus Funding & Structure (Heidrick & Struggles)

- 49% funded from management fees

- 14% funded via portfolio oversight or billables

- 50% use formulaic bonus structures (firm, fund, or individual performance); 50% are discretionary

Background Premiums

- Ex-MBB (McKinsey, Bain, BCG): 8–11% more

- Generalists earn 14% more than functional specialists (Charles Aris)

Carry Vesting & Terms

- 75% vest on straight-line schedules; 4 years most common (34%)

- Clawbacks: 25–66% (highest at MD level)

- Capital contributions: 49–67% required (usually after-tax; some firms offer financing)

Co-Investment Rights

- Eligibility: 57–74% across roles

- Expected return: 2.4x–2.9x

- Highest participation at VP level (74%), indicating its use as a retention + incentive tool

The Compensation Gap With Deal Teams Creates Organizational Dysfunction

The biggest issue isn’t absolute pay—it’s the systemic gap with deal teams. At the same seniority, operating partners often make 70–85% of what deal professionals do, and the disparity in carry is even starker. That fuels resentment, dysfunction, and signals which roles the firm truly values.

Heidrick & Struggles data shows base pay for partners/MDs is similar ($500K–$750K), but bonuses diverge: deal partners get $362K–$1M, ops partners only $123K–$646K. The real chasm is carry: deal teams receive $16.3M–$75M; ops teams get $3M–$15M. At the managing partner level, deal teams can earn $23M–$400M, while ops leads cap out nearer $20M. Heidrick & Struggles, 2024

This gap persists despite operations driving nearly half of value creation today. PwC

Some defend it by pointing to deal origination and board responsibility—yet operating partners increasingly sit on boards and serve on investment committees, and still trail in pay.

The cultural impact is real. Ops partners report feeling like second‑class citizens. One metaphor:

"Deal partners were the kids who traded baseball cards. Operating partners ran the lemonade stand.”

That framing reinforces that deal work is prestige; ops is execution—even though execution drives returns.

Practically, ops views are often overruled. Deal teams “own the P&L,” so when operational insight conflicts with deal assumptions, deal views dominate. CEOs get conflicting signals, and the pay disparity clarifies who has authority.

Board seat policies worsen it. Some firms require ops partners to share board seats; others forbid it. One exec put it bluntly:

“Are you advising me as an advisor or … as my boss? That’s the tension.”

Without aligned economics, decision rights become fuzzy.

Attribution is another battleground. Who gets credit: the deal team for sourcing, or ops for execution? Absent clear frameworks, carry allocation becomes political—not meritocratic.

These misalignments distort strategy. Deal professionals may favor transactions optimized for financial engineering over ones needing operational work, underinvest in ops support, or treat it as an expense—not a value driver.

Some firms break the mold. Bain Capital, since the 1990s, treated ops as a parallel value arm. It now has 115+ operating professionals compensated competitively with deal partners. Vista Equity maintains a 1:1 ratio between operating and investment teams. Those firms report stronger collaboration, more focused value creation, and better performance.

Others lag. Some mid-market firms still use 1099 contractors for ops work—no carry, no alignment. Even when ops is paid from portfolio budgets, the message is clear: ops is second-tier. (Marketing may tout “operational excellence,” but internal comp says otherwise.) LPs are starting to catch this during due diligence—and they see it as a red flag.

The Talent War and Retention Crisis

The private equity industry faces an acute shortage of operating talent just as demand is surging. Peter Tannenbaum, CEO of executive search firm Ramax, captured the urgency:

“I've been in the recruiting space for 30-plus years, and I've never seen a four-year period like what we're going through right now.”

The shortage stems from several converging factors—but compensation has become the central challenge in both recruiting and retaining top-tier operating professionals.

The supply-demand imbalance has multiple drivers. Limited partners increasingly expect firms to field sophisticated operating teams, with 77% of PE firms citing operational expertise as critical to achieving investment outcomes. Median holding periods have reached 5.7 years—the highest since 2000—requiring long-term operational execution. A high interest rate environment makes financial engineering less effective, placing greater weight on operations as the primary driver of value.

At the same time, firms are seeking specialized operators in areas like AI, digital transformation, and tech enablement—domains where talent is inherently limited (Middle Market Growth).

The candidate pool remains constrained. The operating partner role is more established in the U.S. than in Europe or Asia, limiting global scale. Many operating professionals came up during a decade of low interest rates and mild macro volatility, without navigating sustained inflation or deep cycles—leaving a skills gap in today’s market (PwC).

Meanwhile, seasoned executives with multi-cycle experience are rare and command premium packages. Younger talent doesn’t naturally pursue operating roles—career advisors rarely highlight the path, and the industry still lacks visibility compared to investment tracks.

Compensation gaps drive attrition. Former CEOs and COOs who become operating partners often discover they can earn as much or more in corporate roles—with clearer authority, better lifestyle, and equity upside concentrated in one company rather than spread across portfolios. One operating partner described it this way in the Growth Equity Interview Guide:

“Full-contact travel schedule, because they understand driving change means being forward deployed. They have to ramp quickly—on an industry, a company, a set of stakeholders, a value creation plan—and just when they've turned the corner with one company, they get to start over again with the next one.”

Strategy consulting firms actively recruit operating partners, valuing their private equity experience. McKinsey, Bain, and BCG offer more control over client work, schedule flexibility, and potentially higher hourly rates. Others launch boutique advisory firms, join family offices, or lead value creation inside tech companies with equity upside.

Poaching between private equity firms has intensified. When operating partners switch firms, they typically receive 15–25% compensation increases along with more generous carry. The most competitive firms win bidding wars by modernizing their comp models; others struggle. One recruiter noted that searches that once took 3–4 months now take 6–9 as firms fall short of candidate expectations.

The cost of operating partner departures extends far beyond recruiting fees. Portfolio companies mid-project lose critical support. Departing operators take with them institutional knowledge, portfolio context, and key relationships. CEO turnover often correlates with operating partner exits—78% of PE owners cite the pace of change as a major issue in CEO dynamics. Without a strong operating partner to bridge PE expectations and company realities, friction intensifies (Slayton Search).

Succession challenges compound the issue. Many founding operating partners—often former public company CEOs—are nearing retirement. The next generation of operating leaders needs different skillsets, especially around digital, data, and cross-functional transformation. Yet firms lack clear development pipelines. Promotion paths are poorly defined: “partner” vs. “senior operator” remains ambiguous, and junior operators face bottlenecks in advancing.

Retention demands both competitive economics and cultural integration. Operating partners who feel like second fiddle—even if paid well—tend to leave. They want decision rights, board seats, investment committee access, and symbolic parity with deal teams. Firms that solve comp but neglect culture still face turnover. Those that create genuine partnership—with shared economics and respect—see dramatically stronger retention and recruiting.

Carry Participation: The Real Test of Commitment

Carried interest is the clearest signal of how much a firm values its operating talent. Base salaries and bonuses may be generous, but carry drives long-term wealth and reflects true partnership. How much carry operating partners receive, how it compares to deal teams, and the structure of vesting and clawbacks all reveal how seriously a firm views operational value creation.

Data shows wide variation in approach. At the senior level, carry eligibility reaches 80–92%, but actual allocations differ. According to Charles Aris, individual operating partners typically receive 1–3% of total fund carry, compared to 5–15% for deal partners. Some firms create separate carry pools for operating teams (10–20% of total carry), while others integrate them into the general pool.

More sophisticated firms tie directly to operational performance—metrics like EBITDA growth, revenue acceleration, or executive placements. These models help solve attribution challenges and ensure operators share in the value they help create. Still, clean attribution is tough; few wins are purely operational or investment-driven.

Vesting schedules largely mirror those of deal professionals. According to Heidrick & Struggles, 34% of firms use four-year straight-line vesting, with others using five-year terms. Vesting typically starts with the fund’s launch or post-deal close. A few firms stretch vesting to 7–10 years to align with longer hold periods.

Clawbacks introduce real risk. Between 25% and 66% of operating partners have clawback provisions—most common at the managing partner level. These are typically triggered by missed hurdle rates or underperforming assets. The tension: operating partners often receive lower carry but face similar downside exposure, sometimes for decisions they didn’t control.

Capital contributions are required by 49–67% of firms. Most require operators to fund these from after-tax income, though some offer financing. For corporate leaders entering PE, contributions of $100K–$500K+ can be a hurdle not faced by deal partners who’ve already accrued wealth through earlier cycles.

Co-investment rights provide another layer of upside. Charles Aris data shows 57–74% of operators receive co-invest opportunities, with expected returns of 2.4–2.9x. Junior operators typically access deal-by-deal co-invest; senior partners receive fund-level access, signaling trust and tenure.

Carry structure also matters. Deal-level carry directly links upside to results on a single investment—great for accountability, but complex to manage. Fund-level carry encourages collaboration and simplifies admin, but makes attribution fuzzier.

Some firms go further. Transaction success fees (0.25–0.75% of exit proceeds) offer cash upside at the deal level. Others grant direct equity in transformed companies, with vesting tied to exit outcomes. Hybrid models combine baseline carry with multipliers triggered by hitting operational milestones.

At its core, this is a question of parity. If operating partners drive nearly half of value creation, should they earn half the carry? PwC raises the same debate. Some argue deal partners take on more fiduciary risk and bring in capital. But more firms are recognizing that without strong execution, even the best deals won’t deliver.

Models That Are Breaking the Old Paradigm

While many firms still rely on legacy compensation structures, others are fundamentally rethinking how operating partners are valued and rewarded. Emerging models range from full economic parity with deal teams to standalone carry pools and performance-tied incentives that directly align with operational outcomes.

The “true partnership” model represents the clearest break from tradition. In this structure, operating partners receive the same base salary, bonus potential, and carried interest as deal professionals at equivalent seniority. The message is explicit: operations and investing are equally vital. Bain Capital pioneered this model in the 1990s with its Portfolio Group, now more than 115 professionals strong. Senior operating partners at Bain sit on investment committees, co-lead boards, and receive compensation fully aligned with their investment peers (Middle Market Growth).

Another approach uses separate carry pools for operating partners. These pools—typically 10–20% of total fund carry—are distributed based on seniority, portfolio involvement, and performance. By creating a dedicated allocation, firms avoid the politics of splitting from the deal team’s carry and signal meaningful commitment to the operating function. Vista Equity Partners applies a version of this model through its Vista Consulting Group.

Performance-based carry models directly link upside to measurable operational targets like margin expansion, revenue growth, or digital transformation goals. Operators might receive baseline carry plus incremental percentages for achieving predefined results. This model sharpens accountability and rewards value creation, but requires careful calibration to account for market variability and shared responsibility across teams.

Hybrid models blend these elements. Operating partners may receive 40–60% of the carry their deal counterparts get, plus performance bonuses tied to KPIs and co-invest rights in deals they actively support. This mix delivers retention, accountability, and upside—aligned with both firm-wide and deal-level impact.

Transaction success fees are also gaining traction—particularly in firms that can’t offer competitive carry. These fees typically range from 0.25–0.75% of exit proceeds for deals where the operating partner led value creation. For example, a 0.5% fee on a $500M exit translates to $2.5M in compensation. Success fees are often funded through deal fees rather than carry, minimizing internal politics—but can introduce pressure to exit early and debates over who drove value.

Direct equity grants in portfolio companies offer even tighter alignment. Some firms award operating partners 0.5–2% of company equity, vesting over 2–3 years. The model fosters strong alignment with management and encourages full-cycle engagement through exit. However, across multiple companies, this can create administrative complexity and prioritization challenges.

Others have piloted profit-sharing from discrete operational initiatives. When operating partners deliver measurable improvements—like procurement savings or pricing optimization—they may receive a share of first-year gains. Unlike carry, this structure offers quicker rewards and is typically funded at the portfolio level. While generally LP-friendly, it requires airtight tracking to ensure fair attribution.

Ultimately, the most forward-thinking firms integrate compensation with structure, authority, and culture. They involve operating partners in investment decisions from diligence through exit, give them voting rights on partnership matters, and build systems to rigorously measure operational impact.

What separates true innovation from failed experiments isn’t just inventive comp—it’s execution. Firms that offer high carry but deny decision rights, sideline ops in strategy, or fail to track value creation will struggle. Economic alignment only works if it’s matched by real authority and cultural equity.

Why Compensation Structure is Strategic, Not Administrative

Treating operating partner compensation as a strategic priority—not just an HR function—is a foundational mindset shift. Compensation structures signal to LPs where a firm places its bets, clarify authority within portfolio companies, determine the caliber of operating talent a firm can attract and retain, and ultimately reveal whether a firm’s stated commitment to operations translates into execution.

The message to LPs centers around a key question: does the firm pay operating partners from GP management fees with full carry, or are they expensed to portfolio companies and funds? The distinction matters. As PwC notes, LPs recognize that firms willing to reduce partner take-home to invest in operating capabilities show real conviction. During diligence, LPs increasingly ask about comp structures, seeing them as a window into a firm’s true priorities. One LP put it simply:

“LPs are looking for teams that can help transform their underlying portfolio companies for the better… to produce the kind of high-value businesses that can generate the returns they come to private equity for in the first place.”

That conviction translates into performance. McKinsey data shows firms that prioritize operational value creation achieve 2–3 percentage points higher IRR. On a $500M fund, that’s $10–15M in added value—enough to move capital decisions. But claiming operational focus only works if the economics back it up. LPs see through the disconnect when firms tout value creation but keep operators on consultant contracts without carry.

Comp structures also signal authority within the portfolio. When both deal and ops partners show up to board meetings but only one has meaningful carry, CEOs know who holds real power. This undermines the operating partner’s credibility—especially when their recommendations diverge from the deal team’s. As PwC notes, portfolio CEOs often ask:

“Are you advising me as an advisor or as my boss?”

Competitive comp—especially carry—clarifies that operating partners are full partners in the firm’s decision-making.

Recruitment follows suit. Former CEOs, COOs, and senior operators are in short supply and have options: corporate roles, consulting, other PE firms, or family offices. These executives assess opportunities holistically: comp, co-invest, cultural fit, and decision rights. Firms offering true partnership economics consistently attract higher-caliber candidates than those offering consultant-style packages—even if the base is similar.

And the benefits compound. Exceptional operating partners don’t just execute—they expand the firm’s talent network, source executives, recruit junior operators, and build the firm’s rep in operating circles. That positive feedback loop accrues to firms known for treating their operating talent as true partners.

In deal processes, operating capabilities are a growing differentiator. Founders and management teams prefer buyers who will help build—not just flip—the business. When operating partners are part of diligence and deal structuring, not just post-close support, it strengthens a firm’s position. But if the comp structure says ops is secondary, that signal cuts through fast.

Inside the portfolio, compensation clarity has ripple effects. Promoting operating partners to full partnership or expanding their carry sends a strong message to CEOs: operations matter. It signals long-term commitment to value creation. But when operating partners leave for better offers, it destabilizes leadership continuity and sends the opposite message.

These dynamics play out in firm behavior. Where ops comp lags, deal teams default to financial engineering and bolt-ons—faster, cleaner, easier to attribute. Value creation plans become checkboxes, not real strategic blueprints. Even talented operators can’t drive transformation if the economics don’t support it.

But where comp and culture align, firms behave differently. Deal teams source with operational theses in mind. Operating partners help shape the investment case pre-close and lead execution post-close—with real authority and full alignment. Portcos get consistent support. The firm delivers better outcomes not just because of better operators—but because the entire model is built to support them.

The Economics Justify the Investment

The business case for competitive operating partner compensation is straightforward: the returns justify the investment. While base salary, bonus, and carry may appear costly at first glance, they pale in comparison to the value operating partners deliver—and the cost of alternatives.

Consider the math. A senior operating partner earning a $500K base, $250K bonus, and 2% of carry in a $1B fund may receive up to $8–10M over the fund’s life if that carry vests. That sounds significant—until you factor in the value created. A 2% carry share on a 2x return ($1B profit × 20% carry = $200M carry pool × 2%) equals $4M. Meanwhile, McKinsey shows firms focused on operational value creation generate 2–3% higher IRR. On a $1B fund, that’s $20–30M more for LPs. With 20% carry, the GP earns an additional $4–6M—meaning the firm still comes out ahead after paying the operator’s carry. That’s a 3–5x ROI at the fund level—and even higher at the deal level.

At the portfolio level, the impact is even clearer. A 5% EBITDA margin improvement on a $100M revenue company creates $5M in additional EBITDA. At a 10x multiple, that’s $50M in enterprise value. Even a 2% improvement drives $20M in upside. Compared to $750K in annual comp, the payoff is enormous—25x or more—on a single initiative. And most operating partners are managing multiple companies at once.

Retention economics strengthen the case. CEO turnover in PE-backed companies exceeds 70% over a fund’s life. CFO turnover exceeds 80%. Replacing executives costs $500K–$1M per hire—recruitment fees, severance, downtime, delays. Across a ten-company portfolio, that’s $5–8M in churn cost. Operating partners reduce turnover by mentoring leaders, aligning teams, and proactively assessing talent.

The alternative—external consultants—is often more expensive and less effective. A single project may cost $200K–$500K. Multiply that by 3–5 engagements per company and 10 companies per portfolio, and you're looking at $10–20M in consulting spend. Consultants lack continuity, long-term alignment, and carry incentives. They also require deal teams to manage them closely—burning time and attention.

Then there’s opportunity cost. Underpaid operating partners leave. Replacing them takes 6–9 months. In that gap, execution slows, exits delay, and value creation stalls. The performance drag can shave 1–2% off fund returns—$10–20M on a $1B fund—far more than what it costs to pay top talent competitively.

The long-term payoff compounds. Operators who stay through multiple fund cycles develop deep institutional knowledge, mentor junior talent, and expand the firm’s executive network. They strengthen the firm’s reputation and recruiting power—value that’s only captured through retention, which requires comp that grows with tenure and includes meaningful carry.

From the LP’s point of view, competitive comp improves returns without added cost. Unlike increasing management fees, which reduce LP net returns, reallocating existing fee dollars toward operating partners shifts economics within the GP. LPs prefer this because it boosts performance—2–3% higher IRR—without requiring more capital.

This model is especially important now. With median hold periods reaching 5.7 years—the longest since 2000—firms need full-time operating partners who stay engaged from diligence through exit. Consultants can’t span multi-year transformations. Contracted operators lack true alignment. Only fully integrated operating partners with long-term incentives are positioned to see initiatives through to value realization.

Getting Implementation Right

Restructuring operating partner compensation is as much a political and cultural challenge as it is a technical one. Success depends on navigating partner economics, internal resistance, and organizational inertia—with a clear strategy that blends pragmatism with conviction.

The most contentious issue is carry pool allocation. At most firms, carried interest has traditionally gone to deal partners who source and manage investments. Introducing operating partners into that pool dilutes those allocations. As one executive put it:

“GP dollars come out of somebody’s pocket. In smaller funds, those are real economics. The firm has to believe operators deserve a piece.”

To overcome resistance, reframe the conversation around total value creation—not zero-sum splits. Data from McKinsey and PwC shows firms with strong ops capabilities generate 2–3% higher IRR. On a $500M fund, that translates to $10–15M in extra carry—more than enough to share. Operators get a slice of a larger pie, and deal partners often earn more in absolute dollars.

Start small. Phased rollouts reduce friction. Leading firms begin by piloting carry participation on a few high-impact deals with clear success metrics. Once performance is proven, they expand participation across the portfolio. This approach builds credibility and minimizes disruption.

Attribution frameworks are essential for fairness and politics. Establish performance baselines at acquisition, track against targets like EBITDA growth and working capital gains, then quantify value created. A data-driven approach prevents subjective carry debates and builds trust.

Vesting needs to match role. For operating partners working across funds, standard four-year vesting works. For deal-specific operators, vesting should track exit timing. Hybrid models—time-based and deal-based—balance retention and alignment.

Clawbacks should reflect influence. If operators help select investments, standard provisions apply. But if they’re brought in post-close, they shouldn’t bear equal downside for decisions they didn’t make. Structures must align risk with responsibility.

Capital contributions can create barriers. Many operators come from corporate backgrounds without deep carry reserves. Solutions include: pre-tax carry offsets, contribution loans, reduced capital requirements, or phased commitments. Skin in the game shouldn’t block top talent.

But technical fixes alone aren’t enough.

Cultural change is critical. The firm must treat operators as partners in language, practice, and governance:

- Include them in investment committees and comp discussions

- Celebrate ops wins equally with new deals

- Feature them prominently in LP decks

- Create clear decision rights for when ops and deal views diverge

Communication strategy matters. Don’t drop changes without preparation. Leading firms:

- Align senior leadership on the “why”

- Run collaborative sessions with deal teams

- Document the framework before rollout

- Position the change as a strategic investment, not a cost shift

Governance must follow economics. If operators get 15–20% of fund carry, they deserve influence—committee seats, succession input, and a voice in firm direction. Decision frameworks should define when and how operating partners lead, support, or defer.

Timelines matter. Full implementation typically takes 18–36 months:

- Months 0–6: Align leadership, design framework, define metrics

- Months 6–12: Pilot structure on new deals

- Months 12–24+: Scale across the portfolio, integrate into firm culture

Rushing sparks backlash. Delaying loses momentum. Pacing is key.

Finally, accountability systems must track impact. Firms need:

- Operational KPIs for each portco

- Quantified value of operator-led initiatives

- Case studies for LPs

- Retrospectives on exits to isolate drivers of return

This data doesn’t just justify compensation. It sharpens internal clarity and ensures underperformance gets addressed early.

Mistakes Firms Make Repeatedly

Despite growing recognition that competitive compensation matters, many firms repeat predictable missteps—rooted in outdated mindsets, short-term cost focus, and organizational inertia.

1. Treating operating partners like consultants.

The most common mistake is the “consulting firm mindset”: hiring operating partners as 1099 contractors, paying project-based fees expensed to portcos, and offering no benefits or carry. These operators lack long-term alignment, split attention across clients, and aren’t embedded early enough to influence strategy. While this model appears flexible and low-cost, it consistently underdelivers—especially on multi-year transformations.

2. Focusing on cost, not value.

Some firms balk at a $750K comp package without calculating the upside. They ignore the 2–3% IRR differential strong ops can deliver, the $5–10M in value from a single EBITDA improvement, or the costs avoided by reducing CEO/CFO churn. Optimizing for short-term opex instead of long-term fund returns results in underpowered teams—or expensive reliance on consultants.

3. Misaligning compensation and philosophy.

Firms often say operations matter, yet structure comp like they don’t. Common signs:

- Paying ops from portco budgets (not GP fees)

- Allocating little to no carry

- Excluding ops from investment committees

- Maintaining separate partnership tracks

The result? A mixed message: operations are essential, but not integral to the firm.

4. Poor attribution practices.

Asking CEOs or deal partners to evaluate ops impact introduces bias. Better approaches track pre- and post-acquisition performance, tie results to specific initiatives (pricing, procurement, talent), and use third-party reviews post-exit to quantify impact objectively.

5. Failing to integrate ops culturally.

Even well-compensated operators feel like outsiders when:

- They're brought in post-close

- They're excluded from key decisions

- Their input is routinely overridden

- They're physically or symbolically siloed

Comp alone doesn't drive retention—recognition, authority, and inclusion do.

6. Not adapting to longer hold periods.

As hold periods stretch to 5–7 years, comp models built for 3–4 years break down. Firms need longer vesting, stronger retention plans, and increased authority for ops teams who stay embedded with portcos over time.

7. Over-indexing on retired executives.

Relying on former CEOs may look good on paper, but often misses the mark in practice. Many retired leaders lack hands-on intensity, aren't fluent in modern tech and digital levers, and prefer governance roles over execution. Younger, domain-deep operators often outperform with more current skills and day-to-day involvement.

The Path Forward for Mega-Funds

Mega-funds managing $10B+ have both the resources and strategic imperative to build world-class operating capabilities. They face intense LP scrutiny, compete for the most complex deals, and must justify premium valuations through operational execution. As market pace-setters, their compensation practices shape industry norms.

Build scaled, centralized teams.

Top firms like KKR, Blackstone, and Bain Capital already employ 100+ full-time operating professionals within dedicated portfolio operations groups. Teams should be organized by function—finance, tech, talent, procurement, pricing, M&A—and by industry vertical, allowing specialists to match specific portfolio needs.

For a $20B fund, a typical structure might include:

- 10–15 operating partners/managing directors

- 20–30 principals and VPs

- 20–35 associates and analysts

Compensation should reflect parity.

Base salaries for senior operating partners should range from $500K–$750K, with bonuses of $250K–$1M tied to both fund performance and operational KPIs. Carried interest should total 15–20% of the fund’s pool, with individual allocations of 1–3%, depending on role and impact. These professionals should also have standard investment committee seats to influence deal selection and portfolio oversight. Annual operating budgets of $20–40M—roughly 1% of AUM—are appropriate and should be funded from management fees.

Operational excellence must be systematic.

The real differentiator for mega-funds is repeatability at scale. Vista Equity Partners uses a 100+ point playbook to drive transformation across its portfolio. KKR Capstone’s 100-day plans and Green Portfolio Program have delivered billions in value. World-class operating groups should develop their own proprietary frameworks, benchmark dashboards, and training programs to ensure consistency and impact.

Talent is a strategic advantage.

Mega-funds can attract top-tier operators by offering:

- Premium comp

- The prestige of large-scale transformations

- Exposure to best-in-class teams

- Clear career paths to senior partnership

They should target:

- Former public company COOs and CFOs

- High-performing operators from smaller PE firms

- Senior consultants from firms like McKinsey or Bain

- Proven transformation leaders from operating companies

The pitch is simple: the chance to drive impact at scale—with the compensation and resources to match.

Middle-Market Strategies

Mid-market firms ($1–5B AUM) sit in the sweet spot: portfolio companies are big enough for real operational lift, yet small enough for change to drive meaningful returns. While they can't support mega-fund infrastructure, a hybrid model offers the right balance.

Lean core + flexible network.

A central team of 3–8 full-time operating partners provides continuity, institutional knowledge, and firm-wide support. These generalists—former CFOs, digital transformation leads, or human capital experts—serve across companies. Around them, a bench of 15–30 part-time advisors fills gaps in pricing, supply chain, sector expertise, or interim roles.

Comp that motivates without bloating budgets.

- Core team: Base salaries of $350K–$500K, bonuses of $150K–$300K, with 10–15% of fund carry allocated to ops. Individual carry allocations range from 0.75–2%.

- Extended network: Retainers ($25K–$75K), project fees, co-investment rights, or board comp—flexible based on value and involvement.

Success hinges on networks.

Operating partners must also act as talent magnets—maintaining deep relationships with executives, advisors, and functional specialists who can be activated quickly and cost-effectively. This “rolodex leverage” lets mid-market firms outperform their budgetary constraints.

Lower Middle-Market & Emerging Managers

For firms under $1B AUM, constraints are real. Annual management fees ($5–20M) must fund everything—investing, ops, admin, and overhead. Precision is essential.

One or two “super-generalists.”

Rather than a full team, most lean on one or two operating principals with broad capability across finance, ops, tech, and talent. Ideal candidates are former CEOs/COOs or top-tier consultants. Comp typically includes:

- Base salary: $250K–$400K

- Bonus: $100K–$200K

- Carry: 5–10% collectively, allocated deal-by-deal

Selective specialization.

Firms identify 2–3 high-impact focus areas—pricing, infrastructure, coaching—and build deep relationships with 5–10 trusted specialists. Compensation often comes via success fees, board seats, or equity—not cash.

Creative structures stretch impact.

- Fractional roles: One exceptional operator across 2–3 portcos for $200K–$300K

- Regional consulting partnerships: For volume discounts

- MBA talent and tech platforms: Tap low-cost, high-value resources like Catalant

Pitching talent requires repositioning.

While comp is lower, these roles offer autonomy, visibility, and career acceleration. For entrepreneurial operators, it’s often a better fit than mega-fund rigidity.

Confronting Reality and Making Choices

The compensation crisis stems from private equity’s half-measure approach to operational excellence. Everyone acknowledges ops drive returns, but many firms still underpay and under-empower their operating talent.

Firms must choose: is ops core or cosmetic?

- If core: Pay like it. Offer full partnership economics, carry, investment committee seats, and cultural integration.

- If not: Admit it—and outsource as needed.

- The worst path? Pretending ops matter while structuring comp to say otherwise.

The business case is clear.

- McKinsey shows ops-focused firms outperform peers by 2–3% IRR—translating to $10M–$30M in LP value on a $1B fund

- Strong comp reduces turnover, attracts better talent, and signals credibility to LPs

- Operating partners with skin in the game perform better and stay longer

Implementation requires real leadership.

Partners must make space—literally—from their own carry pools. It takes conviction, not lip service. That means:

- Championing ops voices in IC

- Enforcing true decision rights

- Embedding ops in culture and governance

- Backing it with capital—not just comps

The divide is widening.

Firms that act now will attract the best operators, raise easier with LPs, and drive stronger returns. Those that delay will face compounding disadvantages—missed value creation, team attrition, and lost credibility.

The crisis is solvable. But only for firms willing to align economics with reality.